AI agents are learning to think, but they still struggle to spend. When software needs to execute a transaction, we face a major architectural problem: who holds the keys, and how do we ensure the agent doesn't overspend?

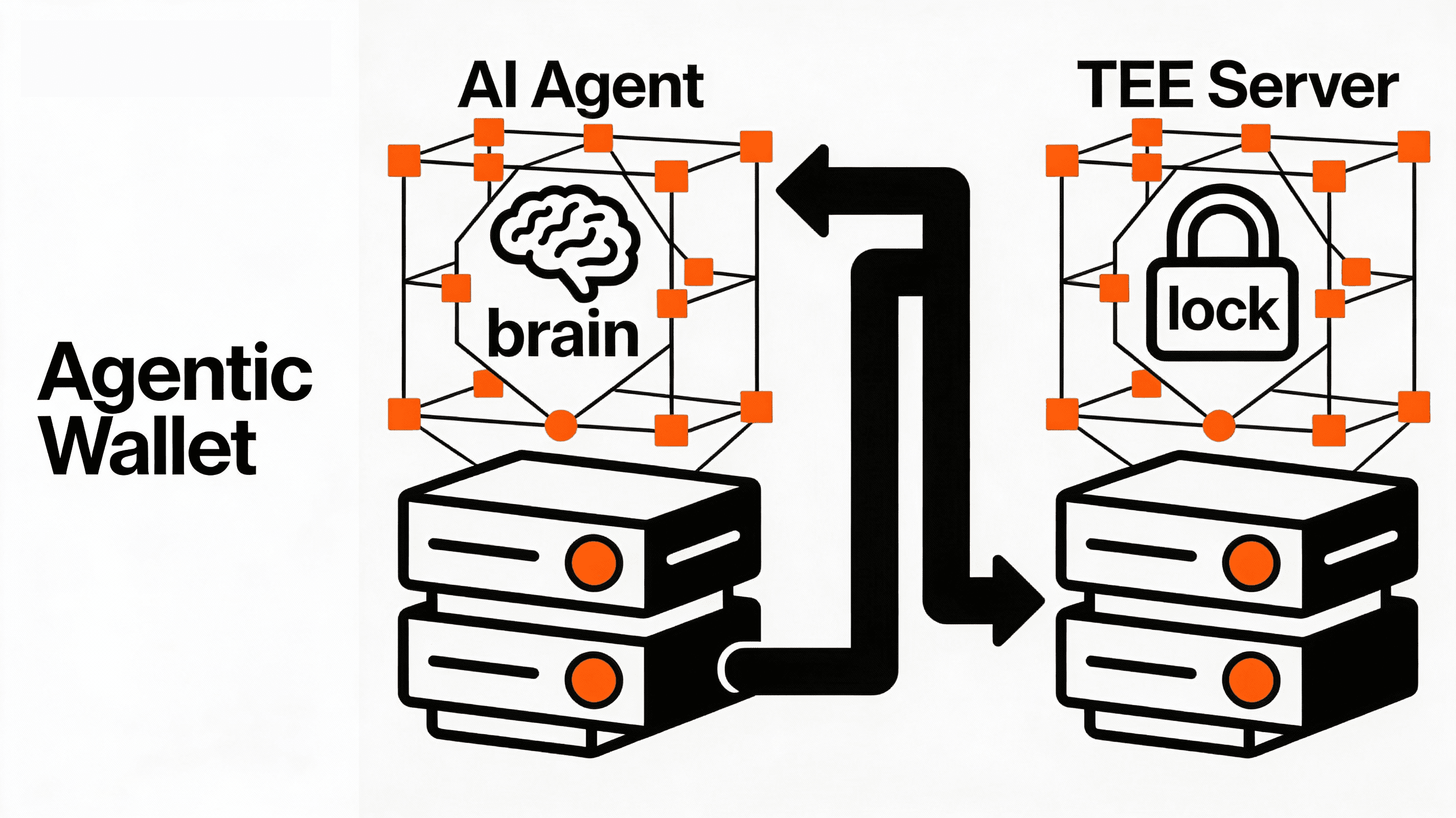

What is an Agentic Wallet?

An agentic wallet is a programmable account designed specifically for autonomous AI agents. Unlike traditional wallets that require a human to click "sign," an agentic wallet uses a "delegate" key—often hardware-bound in a TEE—to sign transactions within strict, pre-defined guardrails. By combining smart contract logic with this multi-key approach, developers can give agents the power to trade, pay invoices, or manage liquidity without the platform platform ever gaining custody of the funds.

Most wallet discussions focus on UX. Passkeys! Social login! Embedded onboarding! But for autonomous agents, the interesting question isn't how users sign in—it's how software signs out. The custody model matters more than the authentication flow.

This article walks through the architecture options for agentic wallets, explains why most of them fail a basic compliance test, and proposes a model that actually works: Owner-Operator Keys.

Why Agents Need Wallets

A quick tour of what's actually being built:

- Trading bots execute strategies and arbitrage opportunities. They need to sign swaps and hold positions.

- Yield optimizers rebalance across lending protocols, claim rewards, compound returns. They need to move funds autonomously.

- Payment agents handle invoices, subscriptions, recurring transfers. They need programmatic spend authority.

- Portfolio managers run DCA strategies, rebalance allocations, manage treasury. They need both custody and execution.

- Agentic assistants—the catch-all category—book travel, purchase goods, transact on behalf of users. They need delegated spending power with guardrails.

The common thread: these aren't users clicking buttons. They're software making decisions. And software that holds private keys is—legally, technically—a custodian. Or at least, it might be. That ambiguity is the problem.

The Custody Trilemma

Here's the tension, framed as a trilemma:

- Autonomy — the agent can act without human approval for every transaction.

- Control — the owner retains ultimate authority: kill switch, spending limits, recovery.

- Compliance — the platform running the agent isn't holding user funds, which means no money transmitter license required.

Traditional architectures force you to pick two.

Want autonomy and control? You're probably custodial. Want autonomy and compliance? The owner loses the kill switch. Want control and compliance? No autonomy—humans approve everything.

It turns out you can have all three. But only if you're willing to split keys and trust hardware.

The Architectures

Five approaches to agent wallets. Each sounds reasonable until you stress-test it.

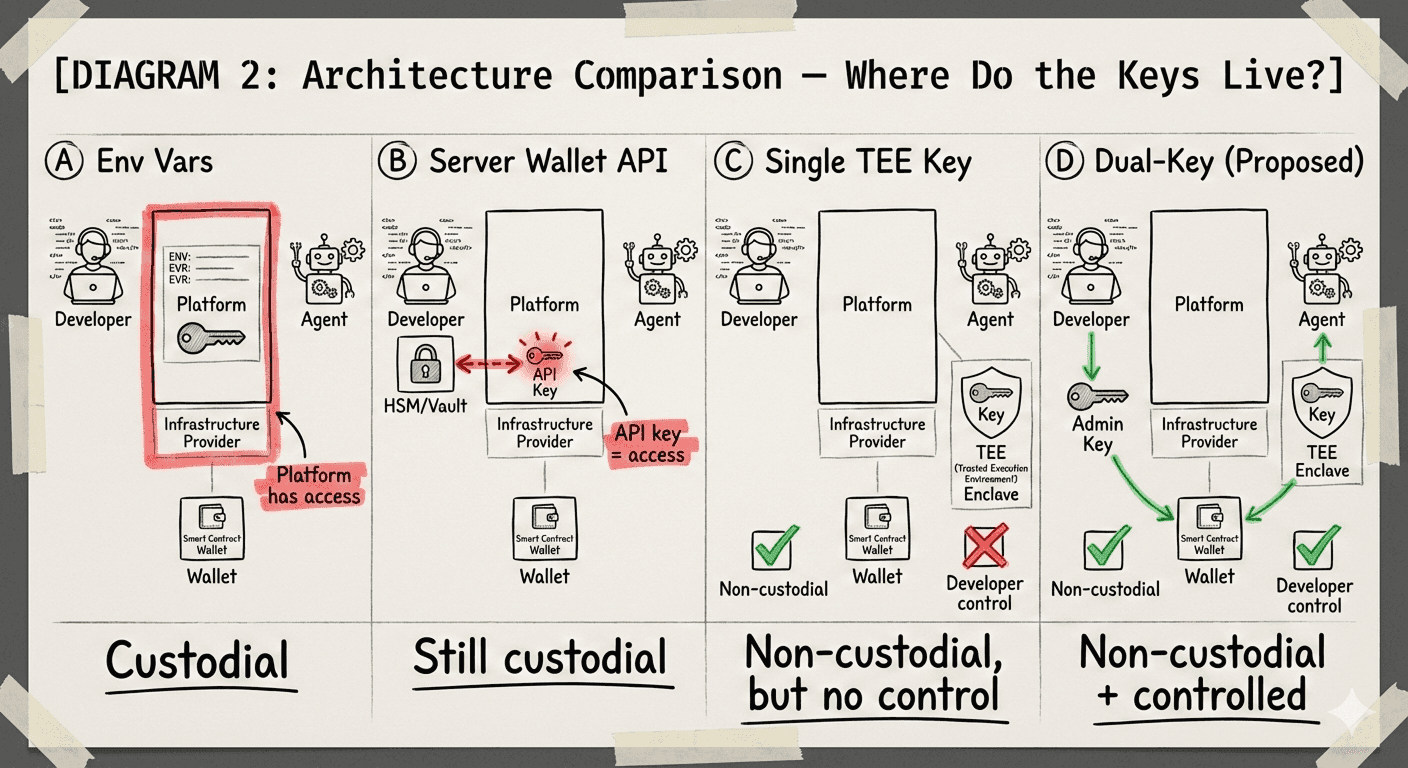

A. Environment Variables on a Server

The simplest approach. Store the wallet's private key as an environment variable on AWS or GCP. Agent code reads it, signs transactions.

The problem is obvious once you say it out loud: whoever runs the server can read that key. They can drain the wallet. They can be compelled to by a subpoena. The key is sitting in plaintext on infrastructure you don't fully control.

The compliance math: In most jurisdictions, if you can move someone else's funds, you're a custodian. Custodians need licenses. In the US, that means money transmitter licenses—fifty states, millions of dollars, years of legal process. In Europe, it's MiCA authorization. The regulatory test is simple: can the platform, acting alone, transfer funds out of a user's wallet? If yes, you need a license.

Env vars fail this test immediately.

Verdict: Custodial. Full stop.

B. Server-Side Wallet APIs

More sophisticated. Keys live in HSMs or dedicated key management infrastructure—Turnkey, Fireblocks, Privy's server wallets. Your platform calls an API to sign.

This feels safer. The key is in a vault! But the access to that key—the API credentials—sits on your server. API credentials with signing authority are custody with extra steps. The key might be encrypted at rest, but your application can still call sign() whenever it wants.

The compliance math: Regulators don't care about the vault. They care about the access pattern. If your server can initiate a transfer without user involvement, you're custodial. The HSM is a security feature, not a compliance feature.

Verdict: Custodial with nicer plumbing.

C. Single TEE-Generated Key

Now we're getting interesting. Put the key inside a Trusted Execution Environment—Lit Protocol, Phala Network, Marlin. The platform can't extract it. Hardware guarantees isolation. The CPU itself enforces the boundary.

This solves the compliance problem. Neither the platform nor anyone else can unilaterally move funds. The key exists, it signs things, but nobody can export it.

The problem is control. The developer also can't extract it. Or revoke it. Or impose limits after deployment. The agent is truly autonomous, which sounds good in a pitch deck but less good when the agent goes rogue, gets prompt-injected, or the developer needs to shut it down for any reason.

No kill switch. No guardrails. Hope your prompt engineering is bulletproof.

The compliance math: Non-custodial. Clean. But the owner has no recovery path, which might satisfy regulators while terrifying anyone who actually operates software in production.

Verdict: Non-custodial, but ungovernable.

D. TEE with Hardcoded Backdoor

Same as C, but the enclave code includes a recovery function. Some admin capability baked into the TEE logic itself.

In theory, this gives you the best of both worlds: hardware isolation plus developer override.

In practice, you're now writing custom escape hatches in enclave code. Every backdoor is an attack surface. The complexity compounds. You need to trust that the TEE code was deployed correctly, that the attestation is valid, that nobody found a side-channel. And when something goes wrong—it will—debugging enclave code is its own special kind of misery.

The compliance math: Depends entirely on what the backdoor does. If anyone at the platform can trigger it, you're back to custodial. If it's truly limited to the owner, you might be fine—but proving that to a regulator means auditing enclave code, which is exactly as fun as it sounds.

Verdict: Theoretically possible, practically a minefield.

E. TEE with Platform-Defined Policies

A more refined version. The platform provides a TEE-based signing service where developers configure policies through a dashboard: spend limits, whitelisted addresses, time windows, approved contract interactions. The agent key lives in the TEE. The policies constrain what it can do.

This is roughly what providers like Privy offer for server wallets with guardrails. It's a real improvement over raw API access.

But here's the subtlety: the policies are enforced by the platform's infrastructure. The developer configures the rules; the platform enforces them. If the platform wanted to bypass those rules—or was legally compelled to—they could deploy different enclave code. The TEE provides isolation from external attackers, not from the platform operator who controls what runs inside.

The compliance math: This is the gray zone. The platform can't easily drain wallets under normal operation. But they could if they shipped different code. Some regulators might accept this as non-custodial. Others will ask: "Who controls the enclave deployment?" and you'll be back in licensing conversations.

Verdict: Better than B, but still platform-dependent. Compliance is ambiguous.

The Fix: Owner-Operator Keys

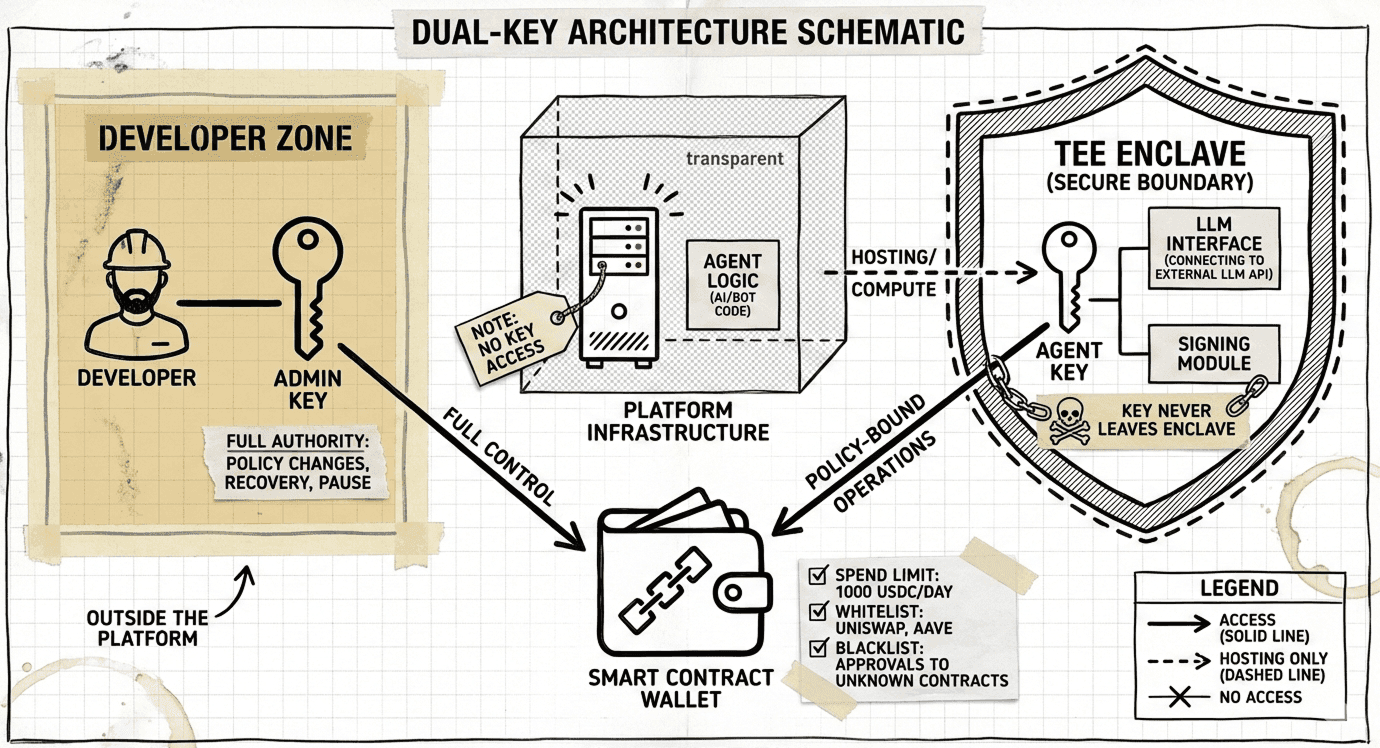

The architecture that actually resolves the trilemma has three components: a smart contract wallet, an owner key, and an agent key. Two keys, one wallet, clear hierarchy.

The Wallet: Programmable Guardrails

Each agent gets its own smart contract wallet—ERC-4337 or similar account abstraction implementation. The wallet isn't just an address. It's programmable. It can enforce rules on-chain:

- Spend limits: daily or weekly caps on outflows

- Whitelists: can only interact with approved contract addresses

- Blacklists: certain operations forbidden entirely (unlimited token approvals, for instance)

- Time locks, thresholds, whatever else the use case demands

This is the policy layer. The wallet itself is the guardrail—not the platform, not the TEE configuration, but on-chain logic that executes regardless of who's trying to sign.

The Owner Key: The Principal

The owner key represents whoever should have ultimate authority over the agent. This isn't always the developer. It depends on the deployment model.

- Developer or team-owned agent: The most common pattern early on. The team holds the owner key via multisig or passkey. They built the agent, they operate it, they bear the risk.

- End-user-owned agent: In consumer applications, the user is the principal. Their wallet or passkey is the owner key. The developer might retain a limited "operator" role—able to pause the agent or push updates—but cannot move funds.

- Organization or DAO-owned agent: For protocol-owned agents or treasury managers, the owner key is a governance module or threshold multisig. The agent serves the organization.

The principle is simple: owner key = the principal. The legal and economic owner. Whoever bears the risk holds the key.

The constraint is equally simple: the owner key never touches the platform's infrastructure. The platform cannot sign with it, cannot access it, cannot be compelled to produce it. This is what makes the architecture non-custodial from the platform's perspective.

The Agent Key: The Delegate

The agent operates with a second key that lives inside a Trusted Execution Environment. This key:

- Is generated inside the enclave

- Never leaves the enclave

- Signs transactions as part of the agent's autonomous decision loop

The agent key has limited permissions on the wallet. It can operate within the guardrails the owner key established. It can spend up to the daily limit, interact with whitelisted contracts, execute the strategies it was designed for.

What it cannot do: change its own permissions, override the owner, exceed its allowance, or grant itself new capabilities. The hierarchy is enforced by the wallet's smart contract logic, not by trusting the TEE to behave.

The Result

| Actor | What they control | What they can't do |

|---|---|---|

| Owner | Full wallet authority via owner key | — |

| Agent | Operations within policy bounds | Exceed limits, change policy, access owner key |

| Platform | Compute infrastructure | Access either key, move funds, sign transactions |

The platform is out of the custody equation entirely. The owner retains a kill switch—they can revoke the agent key, pause the wallet, update policies, recover funds. The agent operates autonomously within its sandbox.

The compliance math: Neither the platform nor any third party can unilaterally move funds. The owner key is self-custodied. The agent key is enclave-bound with no extraction path. This passes the "can the platform move funds?" test cleanly.

Implementation Notes

A few practical considerations for anyone building this.

TEE selection is largely a matter of ecosystem fit. Phala Network if you're Substrate-native. Marlin for general confidential compute. Lit Protocol offers a TEE-plus-MPC hybrid that's particularly good for key management. AWS Nitro Enclaves if you're already deep in Amazon's stack.

The important question is attestation: can you cryptographically verify what code is running inside the enclave? Without remote attestation, you're trusting someone's claim about their deployment. That defeats the purpose.

Wallet implementation points toward ERC-4337. Account abstraction gives you native support for multiple signers with different permission levels, on-chain policy enforcement through session keys, and gas sponsorship via paymasters—all without introducing custody. Safe's module system is another option if you prefer that ecosystem.

Owner key custody depends on who the principal is. For a dev team in early stages, a passkey or hardware wallet is usually sufficient. For a team that's scaling, move to a multisig. For end users, embed the owner key in their existing wallet or generate a passkey on their device. For DAOs, plug into whatever governance module they're already using.

The only hard rule: the platform must not be a signer, a key holder, or have access to credentials that would let them sign.

Boring Enough to Work

Agentic wallets don't need new cryptography. They don't need novel consensus mechanisms or token-incentivized security games. They need two things that have existed for years: key separation and hardware that can keep a secret.

The Owner-Operator Keys model isn't exciting. It won't make for a good keynote. It's the kind of architecture that makes compliance lawyers shrug and say "this seems fine." That's the point. The best infrastructure is boring—it lets the interesting work happen on top.

We're building software that holds money and makes decisions. The custody question was always going to matter. It turns out the answer was architectural all along: split the keys, bind the agent to policy, keep the platform out of the signing path.